2022 Festival Archive: Nick Lehane

Nick Lehane:

Chimpanzee

January 22-24, 2022

Instituto Cervantes Chicago

Presented by Instituto Cervantes Chicago & Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival

Scholarship and Resources

“It’s long been a scientific taboo to endow animals with human emotion but if we do not, we risk missing something fundamental about both animals and us.”

- Frans de Waal (quote supplied by Nick Lehane at the Ellen Van Volkenburg Symposium)

An Essay by Marissa Fenley

Nick Lehane’s Chimpanzee is a heartbreaking exploration of anthropomorphism: our double-sided desire to endow nonhumans with human qualities and to take those endowments away. Chimpanzee follows a “lifetime in the mind of a chimpanzee” over the course of an hour. And specifically, the lifetime of a chimpanzee who was once a part of cross-fostering experiment but is now caged in a testing facility—a real historical phenomenon in the 1960s and 70s which saw several chimps raised among human families, only to be surgically experimented on as a part of pathogen studies once these cross-fostering experiments ended. Lehane masterfully uses the puppetry medium—specifically that of tabletop puppetry, a technique derived from the Japanese tradition of Bunraku—to tell the story of a chimpanzee, confined to a cage, whose torment is interrupted by memories of his foster home.

Lehane uses the medium specificity of table-top puppetry to great effect. The limited, confined space of the table becomes the chimp’s cage, using the claustrophobia inherent to table-top puppetry—a feature that can often be an obstacle for puppeteers trying to maneuver three bodies around a single object—to great dramaturgical effect. However, the chimp also enters into a dreamscape—one where the table becomes a laundry room, a tree in the front yard, a child’s playroom. The chimp’s imaginative escapes never fully transcend the confined space of the table, however; rather they provide a brief moment of relief where we all forget it’s there.

This is not the only way Lehane seamlessly incorporates rather the affective dimensions inherent to table-top puppetry. Without demanding the puppeteers either play explicit dramatic roles (which often feels clunky and competes with the puppetry itself) or serve as cheap metaphors (the puppeteer as God being one of my least favorite), Lehane uses their presence to augment the emotional stakes of his piece. Bunraku—and three-person puppet manipulation in general—offers occasion to inhabit what queer theorist Eve Sedgewick calls “the middle ranges of agency.” 1 While watching a Bunraku production of The Odyssey by Handspring Puppet Company, Sedgewick is struck by how the puppeteers’ control over the puppet is simultaneously dependent on tender devotion. For Sedgewick, the puppeteers inhabit both these affective orientations—one of dominance and one of devotion—at the same time, providing a model for her (in her psychoanalytic idiom) for how to engage both influence over and susceptibility to the world without either annihilating it, or allowing it to annihilate you.

Lehane takes this affective dimension of Bunraku one step further; while he gestures at the possibility of finding the “just right” orientation in between these two extremes of agency, he brutally activates for us the all-too-easy slippage in either direction.

This binary itself—between absolute control and absolute passivity—is a human-made problem. If, as Lehane teaches us, the chimp, “straddles the human and the nonhuman” and can be both “part of the human realm” and made to be a “disposable object,” it is the human that traps him in this liminal space. Lehane lures us into forgetting the puppeteers are there—a credit to his collaborators, Rowan Magee, Andy Manjuck, and Emma Wiseman—allowing us to immerse ourselves in the chimp’s internal world, bathed in soft light such that the puppeteers recede unseen into the darkness. However, the puppeteers assert their influence at select moments, pulling focus ever so slightly by taking away a play toy or tucking the chimp into bed. When the chimp is caged under the harsh florescent light of the testing facility, the puppeteers become the bars of the cage as the chimp shakes them and clammers in desperate hope for freedom. The puppeteers recoil at his blows. They pin him down in his fit of rage, forcefully willing him into submission. Tender devotion becomes violent dominance so fluidly that we almost miss the shift between them. And then the puppeteers recede again, obscuring their role in the chimp puppet’s anthropomorphism and his subsequent dehumanization. In so doing, Lehane allows us to fully believe in the life of the chimp while refusing to let us forget who ultimately determines the conditions of that life.

If, as the above epitaph suggests, we risk missing something if we refuse to endow animals with human emotion, perhaps what we risk missing is not only the best of human impulses—to see ourselves in others—but also the worst—to believe that what we recognize as “ourselves” somehow belongs to us; that our “humanity” is both ours to give and to take away. This brings me to my final point which is that Chimpanzee—as any puppet show about an ape must do—nods at a parallel history of human objectification: that of American slavery and the minstrel show, both of which not only reduced humans to objects, but used ape imagery to do so, often through animated objects. In fact, American puppetry still reproduces such iconography today. 2 Chimpanzee negotiates this living history. During one of the chimp’s reminiscences, we watch him open a toy chest to discover two figurines: one, a mechanical monkey and the other, a white baby doll. The chimp first pulls out the mechanical monkey—an echo of what is known as “Sambo art,” which derives its aesthetics from the minstrel show, for instance, the Monkey Organ Grinder and “Jocko the Ape Negro,” dressed in his bell hop uniform. 3 The monkey toy gives out a muted roar when the chimp shakes it—a noise he finds displeasing so he shuts the monkey away in the box and pushes it away. The chimp then begins playing with the white baby doll, stroking its head and eventually cradling it in his arms. The chimp thus reflects back to us the double-sided impulse of anthropomorphism: the one that endows humanity to those we want to have it—the white child—and takes it away from those we would deny it to—the objectified other.

1 Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “The Weather in Proust.” The Weather in Proust, edited by Jonathan. Goldberg, Duke University Press, 2012, 20.

2 For instance, the logo for the world’s largest ventriloquist convention in Erlanger, Kentucky is “Jacko,” an ape dressed in a bell hop costume, the beloved dummy of W.S. Berger, who founded the convention as well as its museum. “Jacko” is a derivative of Jocko or the “ape negro,” who was a stock character that appeared in countless pantomimes, dramas, minstrel shows and freak shows in the 19th century. The museum displays Jacko, the dummy, in front of a photograph of Berger with his entourage of figures where we see image of Jacko’s forbearer: Jacko the black-face dummy. “Vent Haven Museum–the World’s Only Museum of Ventriloquism.” Venthaven, 2020, https://www.venthaven.org.

3 See: Brown, Bill. “Reification, Reanimation, and the American Uncanny (Spike Lee).” Other Things, The University of Chicago Press, 2019, pp. 245–69. Irelan, Scott R. “White Rebels, ‘Ape Negroes’ and Savage Indians: The Racial Poetics of National Unify in Harry Watkins’s The Pioneer Patriot (1858).” Enacting Nationhood: Identity, Ideology and the Theatre, 1855-99, Cambridge Scholars Pub., 2014, 19.

View Nick Lehane’s presentation above or watch full symposium on Howlround.

Nick Lehane at the Ellen Van Volkenburg Symposium

On Saturday, January 22, 2022, Nick Lehane was a speaker at The Ellen Van Volkenburg Puppetry Symposium session entitled “Staging the Non-Human Character; Animal, Alien, or Architecture.”

The event was co-hosted by The Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival and The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, moderated by Dr. Paulette Richards, and held online through Howlround.

Transcript of Nick's Presentation

Good morning, all. My name is Nick Lehane. It is such a pleasure and an honor to be with you today, albeit digitally. I wish our time could be in person, but I am grateful that this virtual medium makes this talk more accessible. I am going to assume that on the other side of this screen, is some combination of professional puppeteers and diehard puppetry fans, as well as folks who may have never seen a puppet show. So, first of all, what exactly is puppetry?

Puppetry is the use of movement to bring objects to life in the mind of an audience. It’s a broad umbrella term, like dance or music, that encompasses a wide range of traditions and styles and historic functions. There is archaeological evidence that suggests puppets may predate human actors in theater. There are puppets described in the writings of Plato and Aristotle. There are written records of shadow puppetry dating back 3000 years in China, of string puppets 5000 years ago Egypt, the giant puppets used in contemporary Carnival and Mardi Gras celebrations have their roots are not only in medieval European pageantry, but also the habitable statues found in central Africa where manipulators work from within the interior of gigantic figures. There are puppets described in the sacred Hindu text, the Mahabharata. There are dolls with poseable thumbs and fingers used in funerary rights in Pre-columbian central Mexico. The list goes on and on. This ubiquity of puppet and puppet adjacent activities across continents and cultures suggest that our earliest human ancestors shared this strange impulse to animate the inanimate.

And perhaps, more controversially, this impulse appears to have been shared by our pre-human ancestors as well. The peer-reviewed journal Current Biology published in 2010 observations of infant chimpanzees in the wild, caring for sticks and rocks, in ways that appeared similar to the ways human children care for dolls. Puppets indeed come from a very early time, historically. Puppets also reflect a very early time in humans developmentally. They are linked to our early childhood impulses to play, and to what the British psychoanalyst DW Winnecott called transitional objects, like blankies and teddy bears. The first “not me” possessions of the child. And this space between subject and object, between “me” and “not me,” is one of the many ways in which puppets exist between worlds. They are able to live in and bridge gaps. They hover at a threshold– a threshold of the subject and the object, of waking and dreaming, of the conscious and the unconscious, of the sacred and the profane, of the religious and the secular, and germane to this talk, the human and the not human.

In the 1960’s and 70’s, there were a series of experiments in the US where Chimpanzees were raised as children in human homes. They were called cross-fostering experiments, and they are conducted to see how much human language these chimps would acquire, and more broadly, how human they would become. The chimps were raised with American Sign Language, and they learned hundreds of signs. They had access to human toys and picture books, which they would play with much the way human children play. They bonded with their human parents and their siblings, eating meals with their human families at the dinner table. Many enjoyed human so-called “vices” like alcohol and tobacco. One was baptized. And when these chimps matured, they became too powerful or sexual for their humans to handle. Or when funding for these cross-fostering experiments dried up, some of these chimps went on to live as test subjects in a radically different area of scientific research. Pathogen Studies, performed in biomedical facilities. And many were infected with Hepatitis C or HIV, or they underwent surgical procedures to study and change their brains. Most of these chimps were completely physically isolated from all other chimpanzees and humans, locked away with no natural light. The standard cage in a biomedical facility is 5×5 feet. And hundreds of chimpanzees remain warehoused in labs to this day.

I am struck by these stories. Because chimpanzees are, as you probably know, the nonhuman animal closest to humans genetically. And cross fostered chimpanzees are the most culturally human chimps. So that makes these chimps as close as possible to the divide we’ve constructed between human and not human. They straddle the world between us and them. Hovering right in this liminal space between the two. In a single lifetime, some of these chimps experienced inclusion in the sphere of our concern. They were part of the human family. Literally, and metaphorically. And then total exclusion– relegated to the realm of disposable objects. They pass between the container of the suburban family home to the container of the cage. And so, moved by these stories and ideas, and with a team of brilliant collaborators and literally years of support from various artist residencies, and the unwavering support of the Jim Henson Foundation and Cheryl Henson, I created a puppet play called Chimpanzee. And Chimpanzee the play is an hour in a theater, a day in a biomedical facility, and a lifetime in the mind of a chimpanzee. I would like to share excerpts of the piece now. It is about five-minutes long, and it comes towards the beginning of the piece.

(5 minute excerpt of Chimpanzee)

Chimpanzee premiered in New York City in 2019. Thanks to Basil Twist’s HERE Music Puppetry Program. During the run, I met one of the folks who was raised alongside chimpanzees. His name is Joshua Fouts. He is the son of Roger Fouts, the primatologist who wrote the book that originally inspired this project – Next of Kin: My Conversations with Chimpanzees. And Joshua put us in touch with Dr. Mary Lee Jensvold who runs the Fauna Foundation, a chimpanzee sanctuary in Montréal that cares for chimpanzees who have been retired from research facilities. They strive to give these retired chimps as peaceful, supported, and independent an existence as possible, given their circumstances. And it’s not a zoo. So it’s not open to the general public. And when we toured chimpanzee in Montréal, my collaborators and I were given special permission to visit, and many of these chimps had lived lives that directly paralleled the lives of our protagonist. Some of them I had already read about in my research. The show was based on some of these beings. One chimpanzee, named Rachel, was clutching a small stuffed gorilla which she cared for. And Rachel’s nails were painted because it was one of her favorite pastimes. Rachel was on antipsychotic drugs because of the self harm she would inflict as a result of what Dr. Jensvold described as PTSD. I wasn’t familiar with Rachel’s story in particular because she hadn’t been raised in the chimp language experiment, but she had been raised by a human being who considered Rachel her daughter. Until, like so many chimps like her, she grew up and was purchased by a lab, where she spent decades in isolation.

And I think puppetry is a powerful medium to tell these stories because the power of puppetry at its core is the power of empathy. Breaking down and problematizing the barriers and rigid thinking that divides us and them gives us a chance to cross the threshold into another’s experience. Just to follow along with the puppet show, to know what a puppet’s thinking, or feeling, is a massive empathetic leap. And saliently, it is an automatic, largely effortless one. And I think this says something really profound about us– That we can see the world through another being’s eyes by offering our attention. By breathing along with another. Thanks for listening.

Festival Performances

About the Performance

January 22-24, 2022

January 22-24, 2022

Instituto Cervantes of Chicago

31 W. Ohio St. in River North

From award-winning, Brooklyn-based puppet artist and theater maker, Nick Lehane, comes the heartfelt, poignant, and stranger-than-fiction story of a chimpanzee raised as a child in a human home in a cross-fostering experiment conducted in the United States. An exquisite bunraku style puppetry performance breathes in life and illuminates the need for humanity.

With special support from Cheryl Henson

Reviews

People are Hungry for Puppetry by Neil Steinberg, Chicago SunTimes

Philosophical ‘Pooh’ will be just what we need in March by Julian J. Frazin, Chicago Daily Law Bulletin

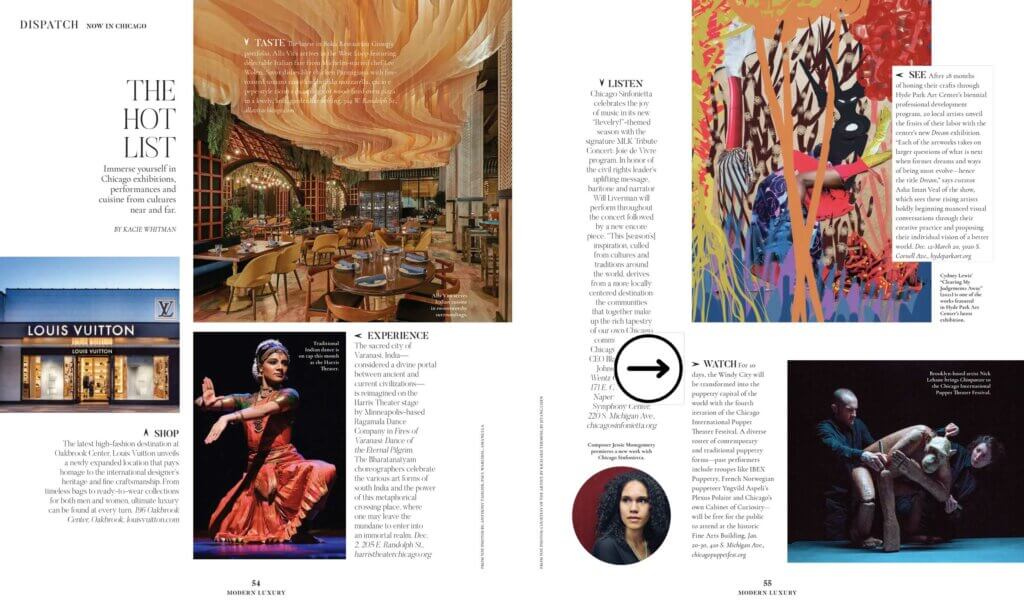

Now in Chicago by Kacie Whitman in Chicago Magazine

Catch Your Breath by Ted C. Fishman in New City

The Fall Living Room Tour Details

Always a wonderful time, each of these intimate fundraisers takes place at a special location with unique food, drink and performance.

The fall prior to the 2022 Festival, Chimpanzee played the Fall Living Room Tour along with Cabinet of Curiosity and Vanessa Valliere at the following homes:

- Jes & Leesa Sherborne at their home, a gracious 1870’s lakefront residence, renovated in the 1930’s to the Italianate Victorian style.

- Hosted by Cheryl Lynn Bruce & Kerry James Marshall at their home, a surprisingly contemporary and totally rebuilt 1883 Victorian in the heart of Chicago’s historic Bronzeville neighborhood.

- Hosted at Manual Cinema at their new studio; originally a machine shop, now a refurbished, heavy timber industrial building, home to Chicago’s shadow puppetry masters and recent Candyman film collaborators. Co-hosted by Kim Ohms & Joe Novelli, Jordan Shields & Sarah Donovan

Enjoy images and video from their appearance at the home of Cheryl Lynn Bruce & Kerry James Marshall. Thanks to Sandra and Michael Perlow for providing special support for the Living Room Tour.

“‘Chimpanzee,’ by Nick Lehane” by Rosie Kelly (The Circus Diaries)

“Chimpanzee Review: Delight and Despair and Transcendence, In the Hands of Humans” – (New York Theater)

“HERE presents Nick Lehane’s Chimpanzee: Puppetry Moves Like No Other Form” by Susan Hall (Berkshire Fine Arts)

“THE HANGOVER REPORT – Nick Lehane’s exquisitely-realized CHIMPANZEE continues HERE’s trend for mounting memorable puppet theater” by drediman (Interludes)

“The Haunting Humanity of a Hominid Puppet” by Elyse Orecchio (Theatre’s Leiter Side)

“Chimpanzee @ The Barbican (London International Mime Festival 2020)” by Charlie Froy (Theatre Full Stop)

“Great Ape: ‘Chimpanzee’ at HERE Arts Center” by Abigail Weil (The Theatre Times)

“Two by HERE’s Dream Puppetry Program” by Alix Cohen (Theater Pizzazz)

“‘Chimpanzee’: alone with her memories” by Christian Saint Pierre (Ledevoir)

“Chimpanzee” (MonTheatre):

“‘Chimpanzee’ by Nick Lehane At the Stables: a puppet show for adults’ by Virginie Chauvette (Bible Urbaine)

“Man raised alongside chimps says it should never happen again” – (New Scientist)

“Puppet Play Chimpanzee, Based on True Events” by Sonia Shechet Epstein (Science and Film)

“Does Anything Awful Happen to the Cat in the Play?” by Laura Collins-Hughes (NY Times)