2023 Festival Archive: Rough House Theater Co.

Rough House Theater Co.: Invitation to a Beheading

January 27-29, 2023

Chopin Theatre

Presented by Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival

Scholarship and Resources

The Dangers of Gnostical Turpitude in Invitation to a Beheading

An Essay by Marissa Fenley

In Rough House Theater’s Invitation to a Beheading¸ adapted from Vladimir Nabokov’s novel of the same title, our protagonist and narrator, Cincinnatus, has been imprisoned for “gnostical turpitude.” Gnosticism, which elevates personal, spiritual knowledge over the material or scientific, gains wicked intent in Nabokov’s telling. While the crime itself is never defined—and indeed Cincinnatus has no idea why he is being imprisoned or when his death sentence will be scheduled—we learn that the pursuit of spiritual truths over those of the material realm is punishable by death in this dystopian world. When reality is no longer anchored in empiricism, one’s imagined and felt realities begin to dangerously distort the environment around them. And such distortions are exactly what Rough House theatricalizes for us.

Gnostical turpitude and its punishments are both, in the hands of Rough House, particularly theatrical offenses. The director, Michael Brown, opens the show as if giving a preshow talk—a conceit familiar to audiences of the Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival, where a member of the staff often prefaces each show with an overview of the festival’s goings-on and a brief introduction to the piece we are about to see. Brown faithfully delivers this preamble true to the form. He goes further, however, and pulls out a copy of Nabokov’s book and begins to read the first page, as if to share some of the source text for the show we are about to see.

However, as his introduction drags on, we begin to realize that the play has already begun. Brown begins to confuse himself with our protagonist. He is then forcibly changed into prison garb—an iconic black-and-white striped tunic—by a stagehand. Brown then opens up the book to reveal a hidden compartment with a puppet of Cincinnatus inside, dressed to replicate Brown’s new costume. A miniature version of the stage set—a bare prison cell—is rolled onstage and the puppet, now in the hands of a stagehand, is used as a proxy for Brown himself, as he is manipulated and coaxed into replicating the movements of his puppet double. Theater’s reality-warping potential poses both a danger to Brown—who has been coerced into the world of his own play—as well as a great power. The world we see is mercilessly shaped by Brown—the actual director of the piece—as well the character he is portraying, whose gnostical turpitude may be to blame for the set of fantastical distortions that make up the rest of the play.

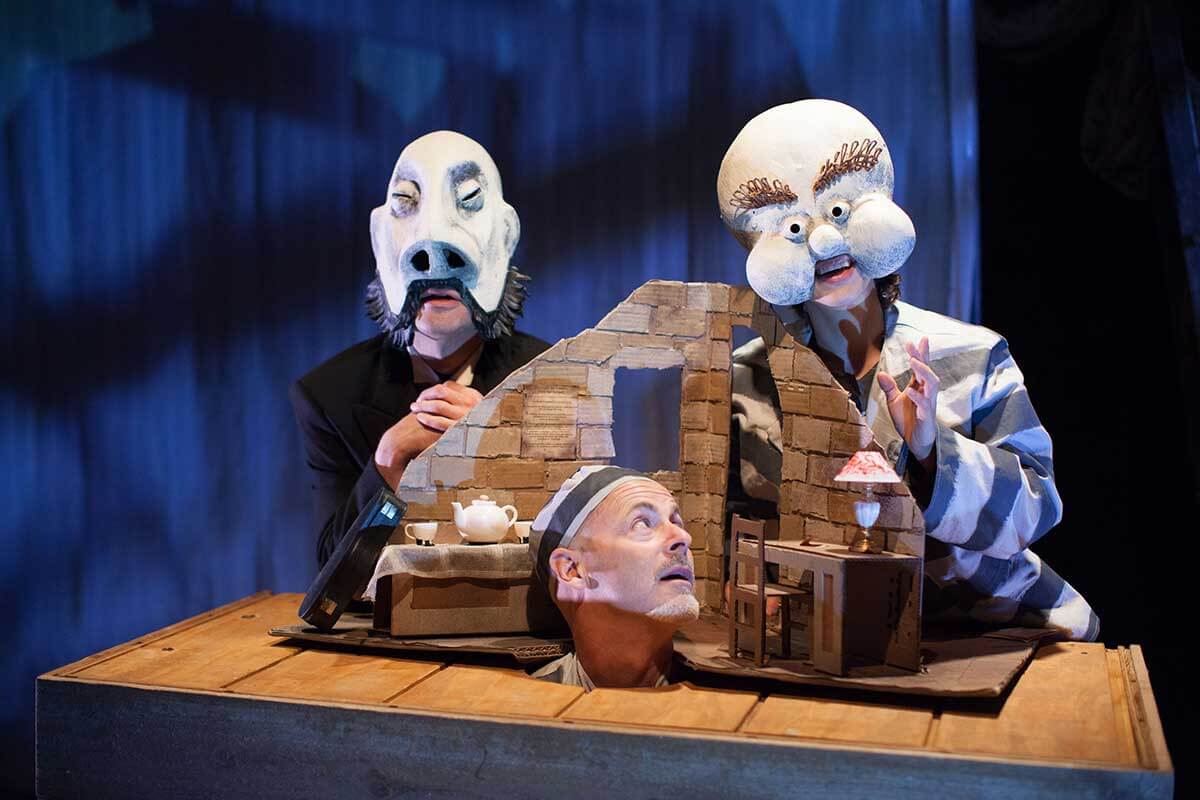

This opening sets up the central conceit of the play: Is Cincinnatus trapped by the theatrical apparatus, or is he the one controlling it? Cincinnatus is not only puppeteered by the stagehands but also acts as a puppeteer himself. For instance, after great prodding, Cincinnatus puppeteers his lawyer, Roman, while the stagehand continues to puppeteer Cincinnatus’s miniature double. And this act doubles as a visual pun on whether or not Cincinnatus will be able to serve as his own self-advocate—will he speak for himself or have others speak for him? Indeed, who is speaking this scene into being? Roman’s exaggerated patrician features (and his characteristic unhelpfulness in aiding Cincinnatus in navigating the legal process or understanding his prison sentence) serve as a recurring motif for the kind of dizzying confusions that abound in this surreal place. Roman’s face is transformed into a full mask and donned by one of our two stagehands (Noah Appelbaum) as Roman becomes Rodion, the jailor, and then Rodrig, the prison director, with no explanation for the many character switches. Our other stagehand (Claire Saxe) is transformed into Cincinnatus’s prison mate, Monsieur Pierre, a vain and nosy fellow who is eventually revealed to be the executioner who carries out Cincinnatus’s death sentence. The audience is left asking: Are such confusions a product of Cincinnatus’s own failure to grasp reality, now lost as he is in his own meditations on his impending death and other spiritual musings? Or are our two stagehands working behind the scenes to bewilder and confuse our poor director/prisoner?

Rough House theatrically transposes the surreal probings of Nabokov’s text into the liminal space between the real and the metaphysical. As Cincinnatus occupies a purgatory between life and death—between a material world and spiritual one—our many ferrymen who usher Cincinnatus across this great divide similarly blur together and occupy many planes. They migrate from puppet forms to full-bodied masked performers. The exaggerated, static masks only add to the feeling that each character is more of an ill-defined figment than real figure. Both mask and puppet give us a corruption of tangible materiality and gesture at what lies behind it. We, alongside Cincinnatus, learn to distrust material reality and instead grasp at the air for something to hold onto. Is there nothing behind the masks but the hallucinations of a dying Cincinnatus? Or are they shadow figures that mystically construct his purgatory? Perhaps, however, they are indeed just two stagehands who orchestrate a delirious piece of theater at the behest—or perhaps at the expense—of their director.

Invitation to a Beheading is currently in the zeitgeist. Uri Singer is currently slated to direct the film adaptation for Universal. When asked what he finds unique about the novel he said: “We consider this to be like ‘Joker’ in reverse, where a mundane protagonist is surrounded by an illogical world” (quoted in Lang, 2021). It would seem that the chaos agent, with his singular capacity for terror and destruction, has fallen out of favor in a chaotic world, whose terrors are unlocalizable and whose origins impossible to trace. In an age of climate change, forever wars, global pandemics, and interlocking refugee crises, the notion of a singular villain speaks less and less to our collective anxieties. Rather, chaos seems to be built into the world around us, and its agents are chimerical: masked and interchangeable. However, Invitation to a Beheading also ushers in a warning: To retreat into the irrealities of our own minds can produce its own kind of chaos—and will ultimately fail to free us from the dangers that encroach upon us.

Works Cited

Lang, Brent. “‘White Noise’ Producer Uri Singer Nabs Rights to Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Invitation to a Beheading’ (EXCLUSIVE),” Variety, September 1, 2021. Available at: https://variety.com/2021/film/news/white-noise-vladimir-nabokov-invitation-to-a-beheading-1235054145/. Accessed July 9, 2023.

Mike Oleon at the Ellen Van Volkenburg Symposium

On Saturday, January 21, 2023, Mike Oleon was a speaker at The Ellen Van Volkenburg Puppetry Symposium session entitled “Grand Narratives and Petits Récits.”

The event was co-hosted by The Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival and The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, moderated by Dr. Paulette Richards, and held at the Studebaker Theater as well as streamed through Howlround.

Transcript of Mike's Presentation

Cool. Well, hi, folks. So my name is Mike Oleon and I am one of the co-artistic directors of Rough House. Rough House is a puppet organization whose mission is to create puppet art that celebrates the weird things that make us unique and the weirder things that bring us together. We started out as a couple of fellow UCLA graduates, who, Los Angeles is fucking weird, and we wanted to go where the theater was, 'cause we thought that's what we went to to school for. So we all moved out to Chicago and we lived in the basement of what we made into a storefront theater that we called "The Rough House."

So that was for about two years, and sort of something that’s been essential to Rough House has always been sort of like interdisciplinary collaboration and community. And so, it’s always had a somewhat like hodgepodgey sort of aesthetic because it’s often been sort of the the product of whoever is in the room… at any given moment. So, right, so we started out where the Rough House itself wasn’t necessarily puppetry focused, but there was, I think we were, we were particularly interested in, in including puppets with, there ended up being sort of a lot of music, a lot of poetry sort of constantly found its way to things, and I think that… Yeah, so I think what I’m, what I’m interested in talking about today is, is some of the things that sort of keep on reasserting themselves in our company that has been around for about 12 years now. We’ve really grown up side by side with Manual Cinema and we’ve, our paths of interwoven in so many different ways. It’s really funny to see some of the, some of the photos where it’s like they’re, they were, I will show you one that is in the exact same space, the same funeral parlor. So, anyway in… So, right, so we started out kind of as very, very sort of hodgepodgey. Oh, and the other thing that really sort of kept on reasserting itself is performance art, which is, I think, distinctly, there is something that is almost always distinctly non-narrative about what we do. We really, I think it could be somewhat to do, there’s certainly a lot of neurodivergent folks in our particular crew and I think that finding one’s path in a single narrative is often very challenging for us. So much of the work that we create involves sort of reaching out into whatever is grabbing us in the moment and incorporating it into things. So in, yeah, ready for the next one? So, this is from one of our first shows that includes, we had sort of a reboot in about 2013 where Claire Saxe and Kay Krone joined us as co-artistic directors of the company. And this was the first show that we did together, which is, “Into the Uncanny Valley.” And this sort of speaks to one of the, one of the first things that really keeps on, keeps on, whether we like it or not, reasserting itself into our work. And that is, I mean, there’s the uncanniness and there’s sort of this otherness that is, yeah, really kind of unavoidable for us. So I’d like you to imagine, briefly, you are a puppeteer, and as a puppeteer you are sort of a, we’ll say a transphasic surgeon, and that you can just sort of reach your hand inside of a human being and pull out an aspect of themselves. And it could be any aspect, it could be, it does have to be essential. It could be a hope, a dream, a fear, a memory, a misremembering, or you could just try and pull out the entire thing and literally have a doppelganger of oneself separated from the original. And I think that’s something that we, we often keep coming back to. And so another thing that is sort of a recurring theme for us is death. Because the puppet itself is, it is, in its own nature, a completely, it is an inert object. It’s an inert object that is entirely dependent on, on human operator for life. And with that theme, you really can’t, you really can’t escape it. Whenever you are doing a puppet show, there is just sort of like, there is always, there’s both the presence of death, and with the presence of death comes this sort of inherent awareness of the preciousness of life and how fleeting it is. And one thing that we really love about puppetry is that it is always this, you know, no matter what show you’re doing, if it’s, you know, from “Sesame Street” to “Frankenstein,” you’ve got, there is sort of always, there is always somewhere on this continuum of how, of how delicate and precious life is and how inevitable death is, you know, and so, so here ready for the next one, so it can exhibit itself as particularly cute. I mean, I don’t know if you necessarily find this cute, but I certainly do. This is Squidbaby, sort of an informal mascot of the company. And, I think when you, when you look at one end of the spectrum and when you shine, when you focus on the light, puppetry is, it’s incredibly, it is empathetic and it is endearing and it has just sort of like baked into its very existence this, sort of, this care for this incredible little miracle that has, you know, popped up for, for between five, and in five minutes and an hour long, or however long the puppet show is, I get squirmy after an hour. So we tend to, we try and keep things short, and so we have, on the one hand we have life of the object and then, on the next one, we have death. We have that other element that lives inside of us, and when you look at it through, through the dark lens, through the shadow, you have, puppets are, it is either endearing that you can bring them up to life or utterly horrifying that you can bring them out of death. This sort of impermeable barrier that no human ever wants to cross. And so, yeah, so these are sort of the strengths that we, we find ourselves constantly playing with in puppetry is both that sort of like endearing nature and also the, the delightful horror that they can conjure. And what’s sort of interesting about some of these, you know, the scarier puppets, is that the more time you spend with them, the more endearing they become. They they lose their haunting power, which is, it is, it’s almost, we have spent so many times trying to avoid that, trying to avoid this sort of like cute-ification that starts to happen over time. And if you could believe it, if you spend enough time with this faceless monster, you know, as we do in our, so Rough House, we’ve been producing these collaborative haunted houses over the last couple of years, five, six years now, and what happens is that when you are hanging out inside of a haunted house, and if you have access to the puppets, if there’s no barrier between you, they lose their frighteningness, which is, it’s really, I don’t know, just kind of like this sublime effect of that there is, it’s like almost like you can’t even fight the empathy that starts to, that starts to develop in, you know, in this this weird puppety stew pot that you’re hanging out in. So, let’s see, yeah, so here we have, here we have a nice little, a puppet, one of our many puppets that was really sort of like meant to be horrifying and really ended up being kind of just endearing instead. So, yeah, this is another one of the haunted houses, and lately the haunted houses have actually switched to, they become a real blend of so many of the different things that we do. So we, so we’ve sort of, we’ve inherited “Nasty Brutish & Short: A Puppet Cabaret,” which was founded by Manual Cinema’s Julia Miller. And it’s really become sort of a core part of the company and how the company relates to each other by, it becomes a platform to be able to share new work, and it’s also, there’s a fantastic puppet expression, which is, “Too short to suck,” which we live and die by.

That sort of short format that the the cabaret provides is a really, it’s a really excellent frame for, for creating… for us, for the puppet haunted house now. And so the haunted house, as it currently exists, is entirely peep shows. So what one does is you walk through the space and there is a box that you approach and there’s holes in, in the exterior of the box and you put on headphones and for the next five minutes you hold your eyes up to the holes and watch a a puppet horror unfold. And what’s really exciting to us about this is that you, is that it gives the individual puppeteers total creative control over their itsy bitsy, little domain, which is, I don’t know, there’s just something so nice about sharing, in particular, that we constantly keep coming back to in creating these, because, you know, within the confines of the box, people can go absolutely wild with their own particular vision, and then, just next door, somebody can be doing something completely different. And just by the sheer fact of putting them side by side, and also in part of the creation, they start to have a conversation with one another. And narrative doesn’t necessarily need to be tied to an existing story in that case because what happens is the audience starts to create a narrative of their own, and you start to, you inevitably start to piece the things together, which is sort of where this exquisite corpse idea comes from for us, is that… “Exquisite Corpse” is a, it’s an absurdist, or surrealist drawing game where you draw one part of a body, you fold it over, pass it to your neighbor and then they, they draw another part of the body without even knowing what’s on the other side of it. And then you get this either creepy or preciously delightful figure that’s waiting for you at the end, or some combination of both, as our stuff often is. So we’ve got, so we’ve got light, death, inescapable empathy, and we can do the do the next one. So this is the one that’s that exact same funeral parlor. And I just, I really love this particular image because, I don’t know, there’s just, there is just such connection that is happening between, between human and puppet. And in that pulling a part of oneself out and being able to examine it, and also to realize how precious that thing is, it really does sort of open up this intuitive awareness that like the other is the self and the self is the other, and boundaries do certainly exist, you know, and they keep us from getting sucked out into space. Boundaries, sometimes, are very good, but sometimes we accidentally create them, and puppets are great because they don’t mind that and they kind of just go trudging through. So, all right, so then the other thing that often sort of finds its way into a lot of our work is, yeah, ready for the next one, is these sort of power dynamics. Power dynamics are often, that is another theme that continually asserts itself, whether we like it or not, in puppetry. And I’m sure because there’s just sort of the factor of, I mean, there’s words like, like “manipulate,” “control,” “master of puppets,” and “master of puppets,” I think, is something that does like a really supreme disservice to puppetry and puppeteers and people’s sort of understanding of how it works because anybody who’s jiggled a puppet or tried to control it or have it do exactly what they want, you know, it is a fool’s game. You cannot master a puppet. If you want to work with a puppet, be a collaborator with the puppet. Puppets, based on the way that they are, are designed based on how heavy it is, how far it’s head turns, the space that you have to put in between like the, you know, just like creating sight lines. There are certain things that the puppet starts to, it starts to assert its own, what feels like, desires. There are things that they’re good at, there’s things that they’re bad at, there’s things that they will absolutely not do under any circumstances. And that’s just, and that’s really just part of it. And so, that narrative of control is another one that reasserts itself. In that, you know, to be a good puppeteer I think that, you know, and it’s taken me a very long time to realize this is that like you have to be a servant to the puppet. You’ve got to… you have to facilitate its life and you have to foster it and you have to do your gosh dang best to be able to make it happen. So this piece is one of our shows called “Ubu the King,” Ubu Roi, created by Alfred Jarry, is sort of a pre-absurdist work about a shitty, shitty man and his shitty, shitty wife and they love to gobble power and ruin everything in the process. And so, for the next one. And so here’s a little screen cap of it in motion, which the, I think Ubu loves to remind us that, that we are not the master of the puppets. If we are indeed puppeteers, like we rely on the puppet for a job. And so, in that sense, it’s really up to us to do, to do it service, to imbue it and to share as much of our life force as we possibly can. And that power dynamic can be what happens when the puppet takes too much life force out of you. You know, when does, when does the relationship tip over… from balance into parasitism? So, yeah, so we explored that with Ubu, which then I guess kind of brings us to, to our show that we have in the festival, “Invitation to a Beheading,” which is, it’s adapted from a novel by Vladimir Nabokov and Michael Brown. They’re rehearsing it right now, which is why I get to be on the panel, ha-ha-ha. Michael Brown is a performer and a physical theater artist, and since I know that the show, I believe, is already sold out, I can reveal to you that it is probably more of a mask show than a puppet show. But we snuck into the festival anyway. And I think that we… It’s been exciting to work with the masks in particular because if we go back to sort of my initial image of being able to reach inside of a human and to be able to pull out an aspect and turn it into a puppet, a mask feels very much like if you stopped halfway through and while the puppet’s still stuck inside of the human’s face, it looks a lot like a mask. And so that’s how we’ve sort of rehearsed and treated this show. And, and I think that the, the masks themselves really inhabit so many of, so many of all of the great elements of puppetry in that they can be something entirely outside of ourselves. And likewise, they can be something that is so human. And in this particular show, they represent, I mean, like, despite the fact that they’re smiling, they actually don’t, they’re not particularly nice masked characters. And, yeah, so that’s been, I think that’s where we’ve gotten to in terms of “Beheading.” And then here’s another picture of “Beheading,” and here we have the, very similarly, sort of this power dynamic that is happening where it’s, you know, who is the master and who is the puppet? It’s, the relationship is far more, far more flexible than I think we often give it credit for. All right, and that is my very long journey across everything. All right, thanks.

Festival Performances

About the Performance

January 27-29, 2023

January 27-29, 2023

The Chopin Theatre (downstairs)

1543 W. Division St.

In a bizarre and irrational world, a man is condemned to death for an absurd crime and sent to a surreal prison to await his execution. But the prison may not be what it seems… Alternately disorienting, absurd, hysterical, and hopeful, this great novel by one of the 20th century’s masters is brought to the stage by Michael Brown and Rough House, with their signature combination of playfulness and strangeness. Full of surprising twists and turns, the novel comes to life through a combination of puppetry, masks, and imaginative storytelling.