2022 Festival Archive: Margaret Laurena Kemp and Janni Younge

Margaret Laurena Kemp and Janni Younge: The Bluest Eye

January 28-30, 2022

The DuSable Museum of African American History

Presented by DuSable Museum of African American History & Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival

Scholarship and Resources

Talismans of Truth

An Essay by Paulette Richards

According to PEN America, legislators in 38 states have introduced 155 bills restricting what teachers can say or teach in their classrooms (Gabbatt, 2022). Between September 2020 and September 2021, the American Library Association (ALA) tracked a 67% increase in the number of attempts to ban school library books (Ujiyedin, 2021). Despite Toni Morrison’s status as a Nobel Prize laureate, her debut novel, The Bluest Eye, regularly appears on the ALA’s list of most-frequently-banned books. Yet director Margaret Laurena Kemp feels strongly that this is a story that must continue to be told. So as the Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum in the pre-pandemic era, she undertook to mount a stage version at the University of California, Davis, where she is a professor in the Theatre and Dance department.

Kemp chose to mount The Bluest Eye at the request of one of the few Black students in her program who praised the book as her favorite novel. Entering her senior year, this talented actor had never had the opportunity to take a lead role because the department had not selected plays with parts for people or color or even opted for colorblind casting. In March 2018, as Kemp was developing the production, Sacramento police officers fired twenty rounds into Stephon Clark, killing the 22-year-old, who was standing in his grandmother’s backyard at the time. The officers claimed they believed the cellphone Clark had in his hand was a gun. Although Kemp received permission to update Lydia Diamond’s 2007 script so that the action of the play would reflect the protagonist Claudia’s efforts to process such traumatic memories, there were not enough African-American student actors at Davis to fill all the roles.

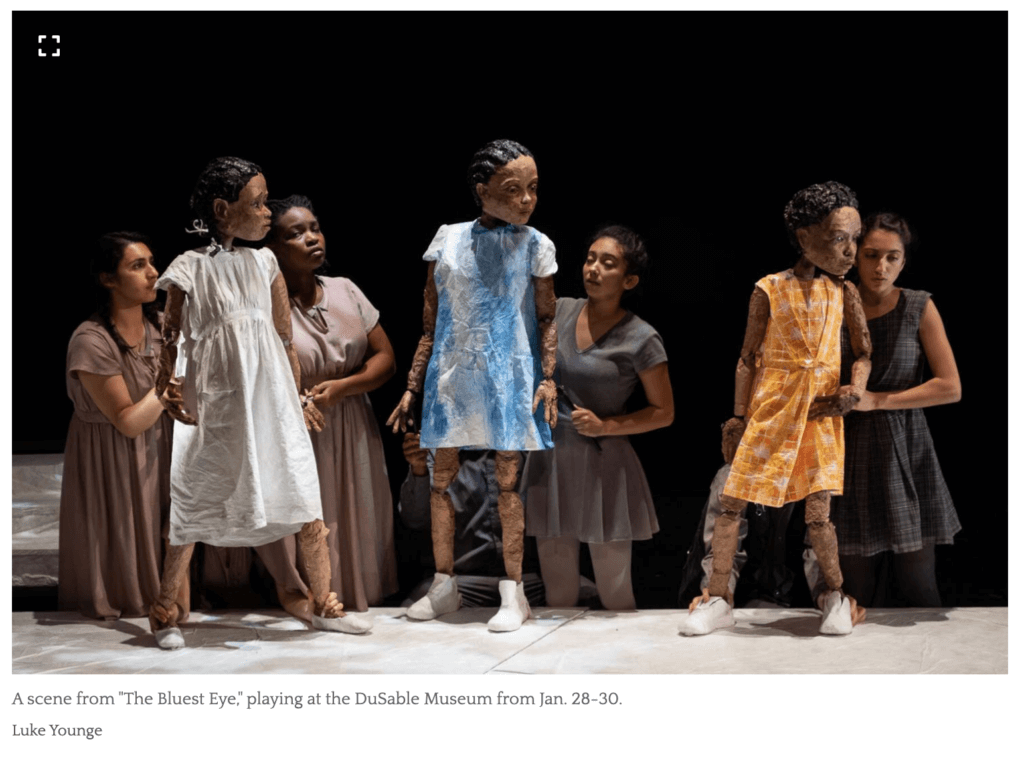

While traveling in South Africa, Kemp had been deeply impressed with the use of puppets in the Truth and Reconciliation process. She, therefore, decided to use puppets in her production of The Bluest Eye. In addition to solving her casting problem, this choice also provided an opportunity for creating a powerful pedagogical experience. Thus, she recruited Janni Younge to design the puppets and co-direct the show. A graduate of the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts de la Marionnette in Charleville Mézières, France, Younge had built puppets and served as the Assistant Director for Handspring Puppet Theater’s Ubu and the Truth Commission. In the process of learning to build and manipulate the Bunraku-style puppets Younge created for The Bluest Eye, the multi-ethnic cast of students absorbed profound lessons about the Black experience in America and about working together to manipulate puppets representing African-American characters. Although Kemp and Younge did not always see eye to eye, still they consciously modeled for the students how they could disagree but continue to work together towards the same goal. The Bluest Eye premiered at UC Davis in May 2018. Along the way the students coalesced as a community and helped raise money to reprise the show at the University of Oregon as part of the Kennedy Center American College Theatre Festival in February 2019, where the production garnered four national citations.

The phase of the journey that brought the show to the Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival was another long, steep climb. The COVID-19 pandemic suspended live theater for the better part of two years. On May 25, 2020, Derek Chauvin, a Minneapolis police officer, murdered George Floyd in full view of a young citizen journalist, who recorded Floyd’s cries on cellphone video, sparking demonstrations and civil unrest across the country and around the world. Then the loser of the intensely divisive presidential election insisted, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that the results were fraudulent and incited his followers to attempt armed insurrection at the Capitol building. These events spurred a national reckoning with inconvenient truths, as well as a concerted campaign of denial from a network of at least 165 local and national groups aiming to disrupt lessons on race and gender equity that they erroneously conflated with “critical race theory (CRT)” (Kingkade, Zadrozny & Collins, 2021).

Traveling, rehearsing and performing before live audiences in Chicago during the Omicron surge of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic presented even more challenges for Kemp’s Bluest Eye team. By this time the original cast members had all graduated and moved on with their lives. The festival version of the play required a smaller cast, so Kemp ended up shifting to an all-female production. Since the stage was smaller, many of the moveable set pieces that functioned as performing objects in the original show had to be left behind, and reanimating the long-dormant theater in the DuSable Black History Museum required additional energy from the cast and crew. The revival drew heavily on the pedagogical exercises Kemp had developed for the UC Davis production.

Kemp’s pedagogical process began with reading. Every cast member read Morrison’s original novel in addition to Diamond’s script adaptation before beginning to imagine the show as a visual storytelling experience. They had weeks and weeks of conversations about race and representation. Opponents of CRT regard such conversations as pretexts for shaming individual whites as racists, yet CRT is a complex methodology that examines how the legal underpinnings of systemic racism in the US produces inequity without individual racist intent. Mastering the subtleties of this analytical approach normally requires graduate-level training, so most K-12 and undergraduate curricula do not apply it. Rather than exacerbating division, reading Morrison’s contested text and moderating frank discussions about race and gender inequity enabled Kemp and her students to build a cohesive community.

Establishing community agreements was essential before the cast ever picked up a puppet. Making room for apologies and space for individuals to step back if they had made an error was one of the most important agreements. The cast was multiracial, but the company realized it was important not to assume identity. For example, during the talk-back after the performance on January 28, one of the cast members responded to a question about the decision to use an all-female cast by pointing out that one of the cast members identifies as nonbinary, although their gender is not visibly marked. Indeed Kemp stresses that the show developed over an extended period of time, so there was space for students to maintain “a simmering pot in the room of things that are troubling them.” She encouraged them to check in with their feelings and add one-word notes to a constellation board so there would be an ongoing language-based conversation about the challenges of doing the work.

Kemp recognized that voice would be the first challenge in the performance. Michael North coined the term “racial ventriloquism” to describe American Modernists’ experimentation with Black dialect in his 1993 monograph, The Dialect of Modernism: Race, Language, and Twentieth-Century Literature. Patricia J. Williams, one of the architects of CRT, subsequently popularized the term as the title for a review of Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace that appeared in The Nation on June 17, 1999. During a roundtable discussion on race and representation in puppetry that was held as part of the festival, Kemp relayed that she was not surprised that actors came to the auditions voicing the characters with what she called “sonic blackface.” She would stop them and instruct, “Just say the words in your voice.” In recent years puppet artists and scholars have recoiled at the history of blackface minstrel puppet performances and questioned whether it is appropriate for puppeteers to manipulate and voice material characters that represent racial identities distinct from their own. Kemp, however, felt that the power of Morrison’s language combined with the puppets could make room for anyone to enter. “We are engaging with these puppets as talismans that allow us to help each other to tell the story,” she explains.

Just as talismans are objects believed to hold spiritual powers, Kemp deployed the puppets as repositories of memory and conceived of the show as a healing space for confronting and reintegrating traumatic history. Like the traumatic memories they reenact, the life-sized puppets are heavy. Coordinating their movements between three operators required concentrated physical effort. The subject matter was equally taxing from an emotional standpoint. Kemp was therefore careful to restrict rehearsals of challenging scenes, such as Cholly’s incestuous rape of Pecola, to once a week so that the performers would not be traumatized.

While some puppet professionals in the audience felt that the cast would have benefitted from more training in manipulating the puppets, the puppets’ movements were engaging. Audiences were deeply moved. They continued to ruminate on the story for days afterwards. While talk backs after the show opened the door to ongoing truth and reconciliation conversations, Kemp’s pedagogical process for staging Morrison’s unflinching gaze at the reality of Black life in the US potentially offers an even more have the opportunity to not only view this production but also to work together while learning to wield books (and puppets) as talismans of truth.

Works Cited

Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival. “Ellen Van Volkenburg Puppetry Symposium: Race and Representation in Puppetry.” HowlRound Theatre Commons. January 29, 2022, https://youtu.be/HCZuuY8MyeQ. Accessed March 29, 2022.

Gabbatt, Adam. “Book Bans and ‘Gag Orders’: The US Schools Crackdown No One Asked For.” The Guardian, Feb. 21, 2022,

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/21/books-bans-gag-orders-suppress-discussion-racism-lgbtq-us-schools. Accessed March 29, 2022.

Kingkade, Tyler, Brandy Zadrozny and Ben Collins. “Critical Race Theory Battle Invades School Boards – With Help from Conservative Groups.” NBC News. June 15, 2021.

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/critical-race-theory-invades-school-boards-help-conservative-groups-n1270794. Accessed March 29, 2022.

North, Michael. The Dialect of Modernism: Race, Language, and Twentieth-Century Literature. Oxford University Press, 1998.

Ujiyedin, Nomin. “There’s New Pressure to Ban Books at Schools.” NPR Morning Edition, hosted by Rachel Martin, KCUR, Kansas City, Dec. 6, 2021, https://www.nprillinois.org/2021-12-06/theres-new-pressure-to-ban-books-at-schools. Accessed July 1, 2022.

Williams, Patricia J. “Racial Ventriloquism.” The Nation. July 17, 1999, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/racial-ventriloquism/. Accessed March 29, 2022.

Margaret Laurena Kemp at the Ellen Van Volkenburg Symposium

On Saturday, January 29, 2022, Margaret Laurena Kemp was a speaker at The Ellen Van Volkenburg Puppetry Symposium session entitled “Race & Representation in Puppetry.”

The event was co-hosted by The Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival and The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, moderated by Dr. Paulette Richards, and held online through Howlround.

Transcript of Margaret's Presentation

Hello everybody. I just wanna thank the festival and my, these wonderful what hopefully one day collaborators that have been talking about their work. Just really, really inspiring and I would sort of like to tell you the form of this. I'm gonna talk and then we'll see a, a clip of The Bluest Eye that you'll hear all about my collaborators and the process in of creating this work.

But I do wanna start, if you don’t mind, Ty, with my paraphrasing you, if you are not dreaming seven generations ahead, you’re not dreaming big enough. And I think that that was really the impulse for my imagining The Bluest Eye as a work for object performance as particularly puppetry. I’m very, a lot of, I do, I’m two things, I’m an artist and I I’m an academic, I have students that I am feel a sense of responsibility for in their, what does it say here? Somebody wrote me something, glasses to see. Boost my sound a little bit, okay, got you. Can you hear me now? Okay, great. Did you hear the quote? I paraphrased Ty, we heard that part, okay, great. So I just wanna say there are two parts of my brain and two parts of the process that we’re in creating this work. One is that I teach, I have students and I’m responsible, I have great deal of responsibility towards them and I’m also an artist and I have great curiosity and longing to create work. And the also important to know that I teach at a majority white institution and, and I come from that kind of training so these are things that are important. And throughout my training, there’s always been very little for me to do in the classroom besides do scene work in class and maybe small roles on occasion if somebody was feeling especially nice to me. And I think that that is, JaMeeka talked about care, that is not the way to care for our students of color. I think it is, I felt that’s a strong responsibility that I take to give my students an opportunity to explore work that is culturally specific for them and challenging for them. So this is where this work arises from. I, and oh, I hope you also heard that show a clip of the work after I talk about it. I’m going to talk about all the way through the process because we didn’t put on a play. We started reading plays and asking questions and The Bluest Eye was just one of many plays that we read, but this was a play that many people responded to, lots of people had questions and lots of different types of people had questions. And I started to really think about how would a community with just, at the most, three African American students, if they wanted to be in it, would be in it? How could we do that? And with a show that required 13 actors, what is a way to do that? And as a lot of theater departments are very siloed. If you’re supposed to teach acting, you just teach acting and you stay quiet, if you’re supposed to teach dance, you just teach the dance and stay quiet. If you’re supposed to do the scenic art, you just do make the set and stay quiet. But as an African American creator, I’ve never had that luxury. And I don’t know many African American creators that do have that luxury to silo themselves. So I was very easily and very quickly able to think broadly about how this story could come to the stage. The students started with study rather than starting with, oh, we’re gonna put on a play. It started with reading The Bluest Eye. Everybody had a copy of the novel, The Bluest Eye. Everyone read the original text that Tony Morris, excuse me, that Lydia Diamond adapted before we moved into thinking about it through visual storytelling. And this is a way of thinking about honoring our elders, our lineage as Ty and Jamila also talked about, bringing the lineage into the classroom. And I think this is important because a lot of people are saying we need to change the canon. But what I actually think is we need to get under the canon and into the roots of the practice and start the change in that place. And in doing that, that’s saying, I’m gonna bring in the lineage. I’m going to say this idea comes from James Baldwin, these movements that we’re doing. I’m thinking about Ensozaki Shenge, continuing to bring in the theatrical legacies and the literary legacies that are as much part of this process as creating the work. So going beyond just putting a play on stage. Our rehearsal process included some ways of approaching work and taking care as Jamila again said, that were developed by artists such as Ping Chong and Company. This idea of of having a constellation, a place where students can have a, a language-based conversation about the challenges of doing the work all the time. This idea of having a simmering pot in the room, things that are troubling them, so they’re actually writing about the process while they’re in the process. And also when we created the original work, we had weeks and weeks and actually years and years where we could have conversations, long ones and small ones about race, about representation, about the fact that there were very few African Americans in the room and students asking, do we have a right to be in this voice? And from that, I’d like to actually spend a little time talking about voice, which was the first thing that I, I knew in the performance was going to be challenging. People came to the audition for this work with a performance of blackness, which was really troubling to me. And most people coming to voice the characters with what I call kind of a sonic blackface. And being able to just stop the students and ask them to just say the words in your voice. Allow us to, what moves you? Why do you want to do this? And just be in your voice and let the power of the language make room for others to enter who may not be black people. Allow them to enter so that they’re not sort of stopped by sort of a shield of behaviors that are not you. So the puppets allowed us to do that, to say this is who we are and we are use engaging with these puppets. And I say as talismans that allow us to help each other to tell this story. While we engage with puppets, I feel that there is also a lot of object performance as part of this work. It was our way, Janni Younge, who is the designer of the puppets and my co-director in this process, because I was reading the book and puppets were using these tables, I started to, started to think about how could these tables be in conversation with the precarity of being black in an urban society where safety is not guaranteed? So training the puppeteers and saying this sidewalk is a place of safety, and then it becomes a place of non-safety. How can we engage with actually the scenery and the props as part of our storytelling as puppeteers and as human beings? The original production had lots of doors all over, yet Pecola Breedlove lives in in a storefront, she doesn’t have privacy. And reminding the students that that is one of the challenges of being black in America, that lack of privacy, that lack of safety. Anybody can come in at any time and challenge your life or take your life. So these are very real conversations that we had. And I wanted to talk a little bit about what was a prologue in the piece and is a prologue in the piece. And I’m going to quote Tony Morrison in Lydia Diamond’s script regarding the world with that we live in. I talk about how it was the fault of the earth, the land, our town, I even think now of the land of the entire country was hostile to Marigolds that year. This soil is bad for certain kinds of flowers, certain seeds it will not nurture, certain fruit it will not bear. And when a land kills of its own volition, we acquiesce and say the victim has no right to live. We are wrong of course, but the ideas pads the fantasy of our strength and disguises the proximity of our own frailty. And I think that that is a final line of the play and it really articulates why we’re it using puppets? This idea of fantasy and reality kind of coming into a polarity and brushing up each other in ways that are, some people say shocking, but this is a world that we live in and asking, can we care? Can we care both as actors on stage, can we hold a place for the black body? And with the puppets, a flesh based actor can hold and make a safe space. And within this performance, there are moments of silence that we have spent a lot of time saying, can we do this? Can we just make a moment and simply hold Percola and say that we can offer her safety.

These are things that were, are important to us as creators of this work and continue, continue to try to find out how we can bring that to the narrative. I’m not sure how much time I have, but I will like to show the video, it’s about three minutes. Do I have time for that, Paulette? Okay, thank you. This is Mrs. Breedlove when she has gives birth to Percola. Our original, and our company still is a multi multiracial company. And I, and this is Austin Brown and Anarita Mukarzo with Claudia. This is a scene where almost the entire cast is engaged in what has become an very tough scene for us to rehearse, it is a scene about humiliation. And in my practice of directing, these are not scenes that we do over and over again. I maybe once, maybe once a week. These are not things that we take lightly in how they impact both the actor in their bodies as well as their, their mental archive, their spiritual archive, so that they are not to the best of our ability, that we are not asking them to continue to perform trauma in a rehearsal process. And next, please. And this is another scene with another puppet. Some of our puppets are full body puppets and some of the puppets are only parts of the body because we are coming to this play from the point of memory, the point of archive. And as an individual, if your flesh is the archive, sometimes there are details that are missing. So I just wanna credit strongly credit Janni Younge in her very careful exploration and questioning of what remains in the memory. Next slide please. And this is Jasmine Washington. And again, Anarita Mukarzo and Jasmine Washington was one of my students when I started the process, I think in her junior year, and we were finally able to bring it into the stage in her senior year, and I actually credit Jasmine. If it hadn’t been for Jasmine and the fact that I had faith in her ability to be an actress, that we would not have gone, I would not have done it because I had this student who, who needed an exploration to allow her gifts as an actor to come to full fruition, so thank you. And next. And this is the articulation of Percola. I did not have an intention of casting three actors in the role of Percola. The first actor I cast is Tiffany Nuongo, who is in the back, and these other actors came to me actually. I recall them coming to my office and putting a fight in for the role saying that they were actually Percola and that I had, I had overlooked the fact that they are Percola. So this became, even while it is a smaller puppet, they be, I asked Janni while she was still in South Africa where this conversation with using puppets, if it was possible for us to have three actors voicing the puppet. And within the text, the text is divided among these three actors. And most often, not at the end of the thought, but right in the middle of the thought or at the beginning of the thought. Because often that’s where the impulse to speak or the impulse to move is. And in this way, I was able to draw in Tony Morrison’s use of music as part of The Bluest Eye storytelling and certainly across the canon of her work and wherever I could thinking about what’s happening in jazz where Soaphead Church is one of the characters in The Bluest Eye, but also in jazz. How can we bring in other elements of this cannon that I’m vested in preserving to the stage? Next side, please.

Why is it only black lives and not all lives? That’s what I’m saying.

Because if Kevon Clark was Stephen Clarkson, you’d be having a very different conversation.

Here is the family, mother, father, Dick and Jane live in the green and white house. See Jane, she has a red dress, who will play with Jane?

There was enough love in our household to give a little to Percola who was sorely in need of someone to care.

They’re very happy.

Crazy, fools messed up my floor, Look at what you did.

Mama said you are here ’cause your mama and daddy went at it and then your daddy went up your house and now you’re outdoor.

Claudia.

What?

It’s true. It’s true, isn’t it?

I ate outdoors, you just stayed away for a minute, Mrs. Breedlove did some things around the house.

I knew this was a falsehood, we have heard people talking.

Girl, you heard about the green looks.

Lord knows if it’s not one thing with bad people, it’s another.

You cut yourself, look, it’s on your dress. Oh don’t cry.

Oh lordy, I knew what that is. You menstruating.

Am I gonna die?

No, you’re not gonna die. That just means you can have a baby.

That true, I can have a baby now?

Sure, sure you can. But how?

Somebody has to love you. Oh, how you do it?

What?

How do you get somebody to love you?

Please God, blue eyes like Shirley Temple or Barbie.

Oh yes, yes looks good.

It happens.

And so is the ugly untidy halibut.

It’s not my fault.

Are my eyes really very nice?

Really truly bluey nice.

Really truly bluey nice, the truly most eye.

So it’s been a long journey and I gotta tell you, we’ve had some bumps in the road. But I also want to say that one of the things that Janni and I really wanted to model between the two of us collaborators, first across oceans and time that it’s okay to have bumps in the road and it’s okay to be challenged in the moment of creativity and how can we model for our students, how can we disagree and still create and be respectful of one another in the process? Thank you. Okay, I’ll hand it to you Paulette.

Festival Performances

About the Performance

January 28-30, 2022

January 28-30, 2022

The DuSable Museum of African American History

740 E. 56th Place in Hyde Park

Co-created and directed by Janni Younge and Margaret Laurena Kemp. Adapted by Lydia Diamond from Toni Morrison’s 1970 book.

Innovative puppetry brings Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison’s coming of age novel into a contemporary context. Pecola is a black girl caught in tragic circumstances. Her best friend narrates her search for the source of responsibility and for an understanding of her own part in the story. The production interrogates how identity is shaped, using a synthesis of puppets, puppeteers and actors. Celebrated South African artist Janni Younge’s puppetry highlights the formation and fragility of self, literally building the self as it is held and supported (or not supported) by a community at large.

With special support from the Paul M. Angell Foundation, Cheryl Lynn Bruce & Kerry James Marshall, Kristy & Brandon Moran. Co-produced by UC Davis & Janni Younge Productions.

Produced by special arrangement with THE DRAMATIC PUBLISHING COMPANY of Woodstock, Illinois

Reviews

DuSable Musem Forges New Theatrical Partnerships by Anne Spiselman, Hyde Park Herald

DuSable Museum and The Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival presents Toni Morrison’s ‘The Bluest Eye’ by Raymond Ward, The Chicago Crusader